As long as I have myself a little soapbox here on the Internet, I might as well diversify my repertoire so I’m not just making fun of Ted Cruz all the time. Welcome to #Content About #Content, where I will occasionally talk about things I like and why I like them.

With love,

Dr. #Content

Alan Wake vanished from digital gaming storefronts last week, a victim of—of all things—an expiring music license. An unusual fate, albeit hardly unheard of; a sad end for an underappreciated classic, and an ironic one. Alan Wake, which owes so much of is success precisely to how details like the music fleshed out its world, by that same music undone. Now it risks fading into history, loved by many but never having earned the universal-classic status afforded contemporaries like BioShock or Dark Souls. It’s time to give Alan Wake its due. It manages something very few games have: it creates an incredible, tangible place, a setting less suited for playing through than for existing in. It pulls that elusive trick of making you believe it wasn’t solely crafted for your playing consumption. The world of Alan Wake is nuanced, believable, alive—rare things in a scene of worlds crafted solely for the player’s action.

(Some context: Alan Wake’s eponymous protagonist, a famous author who hasn’t been able to write a word in years, travels with his wife to to Bright Falls, Washington, hoping to unwind and maybe restore his creative spark. Naturally, everything goes belly-up: Alice disappears; Alan wakes up (ha!) unable to remember his past week; malevolent, shadowy figures chase him through the night; he finds pages of a book he doesn’t remember writing, and they start coming true.)

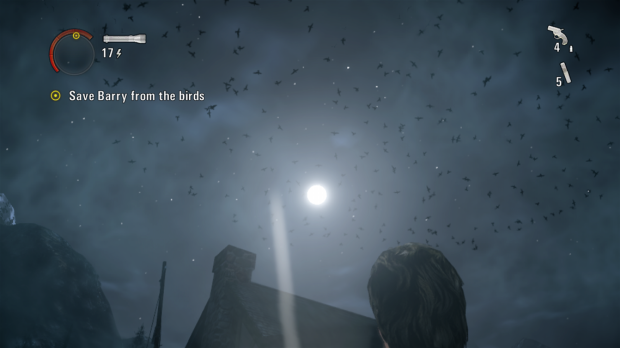

Alan Wake’s world-building occurs on several levels. The first is already evident here, in the very first frame of the game. The nighttime is dark and oppressive. The wind howls through the trees. Every stirring shadow, glimpsed through the roiling fog, threatens something monstrous. A malevolent dark force nips at your heels, and all you have to hold them off is a flashlight, a gun, and perhaps some flares. Rare and distant lights are your only hope of reprieve. And so you run, constantly, for the next one.

These nighttime scenes are the prime examples of some truly outstanding visual artistry. Alan Wake was hardly a graphical showpiece even upon its release seven years ago—later on I have some screenshots of daytime scenes that really show the game’s age—but developer Remedy Entertainment knew the strengths of their graphics engine, and did they ever play to them. At night, it feels at times like every single frame can be printed out and framed.

It’s a good thing that Alan Wake’s dark forests and crow-infested skies are so gorgeous to behold, because to give in to the temptation to run past them would be to miss the subtler work that makes the setting so remarkable. Even the game’s signage, the sort of throwaway detail that Remedy could easily have overlooked, is a labor of love: it’s authentic enough that, first playing Alan Wake threw me back to summer vacations on the West Coast. I particularly like this map, which you find after running through the woods for a while—it gives off that exciting sense of “wow, I went past all that!”

This intricacy and detail conveys a deeper sense that Bright Falls’ reality extends beyond you. The town’s history and character is never shortchanged: it informs, shapes, and lends authenticity to every scene. You spend most of your time in the Elderwood level, for instance, sprinting through the forest at midnight, but nonetheless it is full of historical tidbits and tourist traps like this, things meant to be enjoyed in the light of day:

Bright Falls, for all the madness that engulfs this hapless visitor, is still a town of many quirks, of local people, local prides, local routines. The parks still expect tourists in the morning. The trains still need to run on time.

Moments like this help the world feel alive, but lots of games can manage that for moments, for fits and spurts. What sets Alan Wake apart is the extraordinary completeness of its rendering—every layer of the town’s personality, its history, its atmosphere, has been constructed with care, detail, and authenticity. In the daytime, as Alan tries to learn where Alice has gone before he inevitably ends up in another spooky forest, the pace slows, and you can soak it all in—chat to the locals in a diner, check out archaeology exhibits, read to your heart’s content about the town’s (again, remarkably thoroughly realized) history at the old coal mine, now a museum.

In these quiet moments, you also get to meet the people of Bright Falls—and it’s they who bring the final dimension to the Alan Wake experience. They live the town’s traditions and its history, speaking in excited tones about the upcoming Deerfest or in hushed tones about what happened years ago at Cauldron Lake. They portray in turns both small-town hospitality and insularity; some welcome Alan and his wife enthusiastically, others decry them as big-city yuppies. And, of course, no small town with a questionable past is complete without a few eccentrics: Cynthia Weaver, who prowls the town making sure that no lights have burned out; the Anderson brothers, a lovable pair of ex-rock stars gone soft.

The people fill out familiar tropes, for sure, but that familiarity is warm, comforting, welcoming. There’s no better example of this than Pat Maine’s all-night radio show, where every caller is a regular and no matter too insignificant. He talks about an incoming storm, spreads the word about a missing dog, reminisces about an old love; and always signs off with a cut from the game’s excellent soundtrack (more on that later). In Alan Wake‘s darker moments, Maine’s show is a beacon, an oasis of something friendly and wholesome. It represents the people of Bright Falls through the lonely nights, with a warmth and compassion that makes you all the more appreciative of them during the day.

It all means that, when the residents of Bright Falls inevitably get caught in the crossfire, it’s all the more tragic. The dark forces chasing Alan don’t care about collateral damage. Rose, a local girl, is an early victim. A massive fan of Alan’s books, she’s easily manipulated into attempting to trap him in her home. Alan escapes, but Rose is left a mumbling husk. Before leaving her home, you can look into her bedroom, another example of how carefully Remedy has crafted every facet of this world. It bursts with a joviality and innocence which, it seems, has forever departed:

Playing through the game a second time is, at points, harrowing. Knowing what’s ahead for Rusty, the kindly park ranger, watching him lovingly bandage up the leg of an injured dog is heartbreaking.

A quick note on the soundtrack, which serves as the icing on the cake, a final dose of charm and style to round things off. Selections from the licensed soundtrack, the cause of the game’s demise, cap off each radio broadcast and each in-game episode with panache: the end of Episode 2 singlehandedly made me a Poe fan. Petri Alanko complements this with a wonderful, poignant orchestral score, gorgeous in the hopeful moments and tense in the darker ones. Finnish rockers Poets of the Fall, longtime collaborators with Remedy, put in a delightful turn as the Anderson brothers’ old band.

In other areas, of course, Alan Wake is far from perfect (the second half of the game is not as good as the first; Alan has an annoying habit of narrating over everything; and good God, has the facial animation ever aged horribly), but it’s such a remarkable achievement of world building that a lot of its niggling issues are a moot point—or, in some cases, perhaps actually a point in its favor. One of the game’s stranger stylistic choices is how it gives you explicit visual and audio cues to let you know you’ve finished any given combat encounter. It’s an odd move for a self-proclaimed horror game—knowing no more enemies are around necessarily sucks away much of the tension. But, eventually, I realized it has a purpose. It’s an indicator that you can relax, that you can stop. Let your guard down. Explore for a minute. Perhaps put on one of Pat Maine’s radio programs. Take a moment, before you inevitably plunge back into the darkness, to just exist in this wonderfully realized world.

Remedy are trying to resolve the licensing issue, so perhaps Alan Wake will one day return to digital shelves. In the meantime, you might be able to find a used copy somewhere. If not, Alan Wake’s American Nightmare, a shorter, slightly pulpier sequel, is still available for sale. Its setting is different—a dark, two-lane desert highway—but it is itself beautiful, vibrant, and rich.

This is not a paid endorsement or anything. I just really love this game and want to make sure you know how to get your hands on it if that’s something you want to do now.